While we’re on the subject of mining and mining scrapbooks (that’s still on display at the Museum until 4:00 today) let’s get a little sidetracked with mining maps!

The one at the top of the page is part of Perry’s mining map, from 1893. It was drawn by C.E Perry and Co., a civil engineering firm in Nelson at the heyday of Nelson’s early mining boom. It doesn’t refer to any of the communities in the Creston Valley – mainly because they didn’t exist in 1893 – but it does show the location of Chambers City, at the south end of Duck Lake, which was a stagecoach stop on the route to Bonners Ferry. It also shows a number of other locations with long-forgotten names. Ours is a mere partial photocopy, and not a particularly good one at that – but it’s highly unlikely we’re going to get our hands on an original. Check out this story by Greg Nesteroff, and if you want to see a really high-resolution online version of the map, click here.

Perry’s map makes note of quite a few mining claims, but none in and around Creston. Again, there’s a very good reason for that: Creston Valley seems to have largely lost out in the mineral-wealth lottery. There was a ton (well, thousands of tons, actually, if you take that literally) of silver, lead, and later zinc in the areas surrounding Kootenay Lake; gold in a few places such as Rossland and Golden; coal to the east in the Crowsnest Pass; and quite a few rich mining areas south of the border – but in the Creston Valley, despite many prospectors trying their luck on every promising creek or outcropping, we did not have much of a mining industry at all.

Pretty much the largest mine in the Creston Valley was the Alice Mine, staked in 1890 by a guy named Jack King. Jack King lacked the resources to develop the mine and, like so many other claims, the Alice changed hands pretty regularly – three times in the first eleven years of its existence, and in all that time shipped only one car-load of ore to the smelter at trail (in 1901).

In 1903, though, the federal government began offering high prices for lead, and the following year, the Alice Mine, by now in the hands of its fifth owner, Hubert Mayhew, finally came into production. Mayhew’s nephew, Guy Constable, came out from England to take charge of it. Before long a concentrator was built, complete with an aerial tramway to haul the ore from the mine at the top of Goat Mountain down to the concentrator at the bottom; the CPR built a spur line into the concentrator; and 450 tons of seventy-percent lead were ready to ship.

Despite all this, though, the whole operation of the mine never rose much above the subsistence level, and even that was sporadic: all but shut down by 1914, the First World War and the demand for raw materials it brought gave a new lease on life to the Alice Mine, but it was up for sale again by 1920. There was a little poking around in 1925, and again in the early 1950s – mostly processing the mine dump left from the earlier work – but nothing since.

All told, the Alice mine produced over 509,000 kilograms of lead, 538 kilograms of silver, 473 kilos of zinc, four kilos of copper, and sixty-two grams of gold.

The renewed interest in the mine in the early 1950s, though, did result in a couple of maps that are now in the archives’ collection:

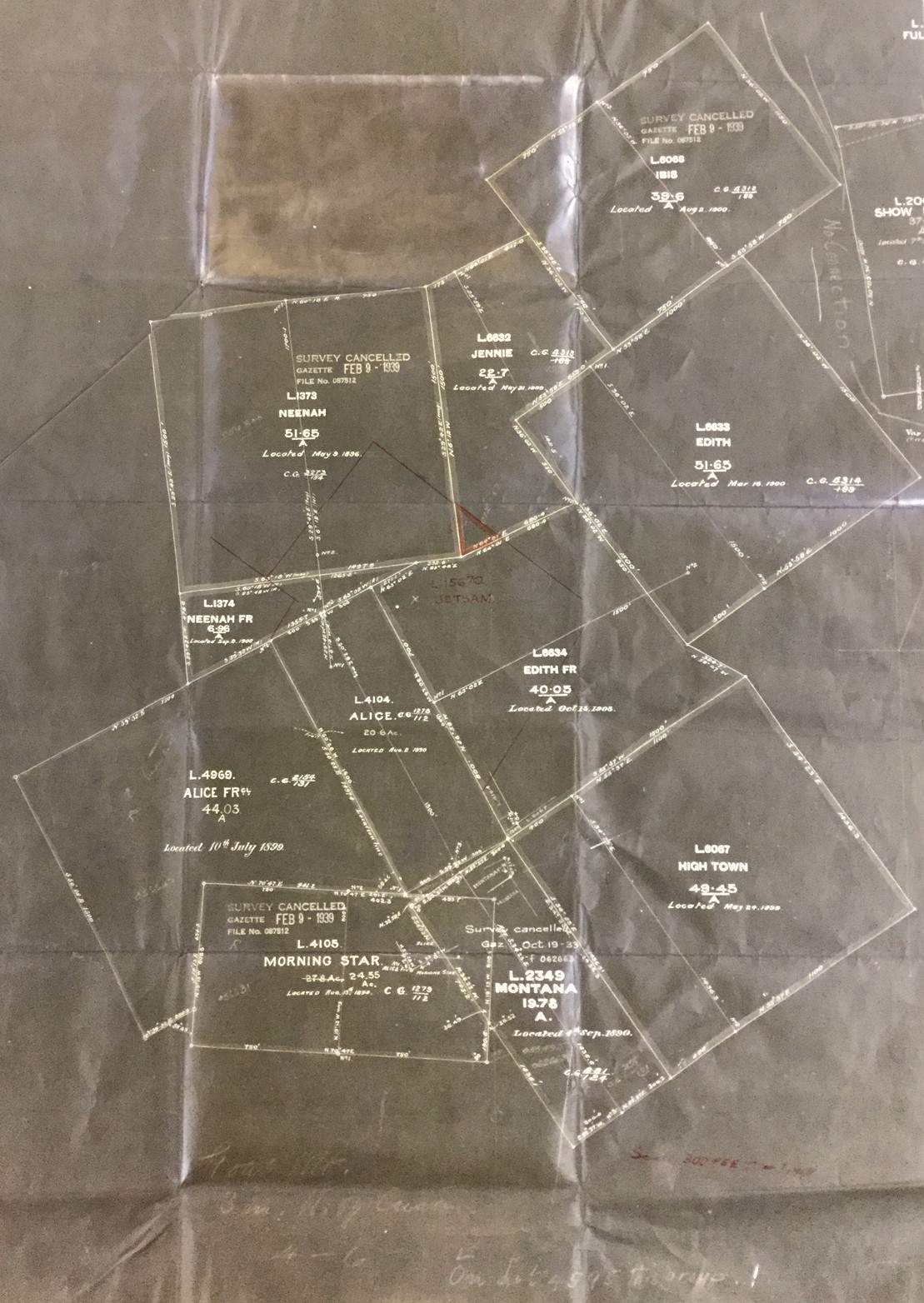

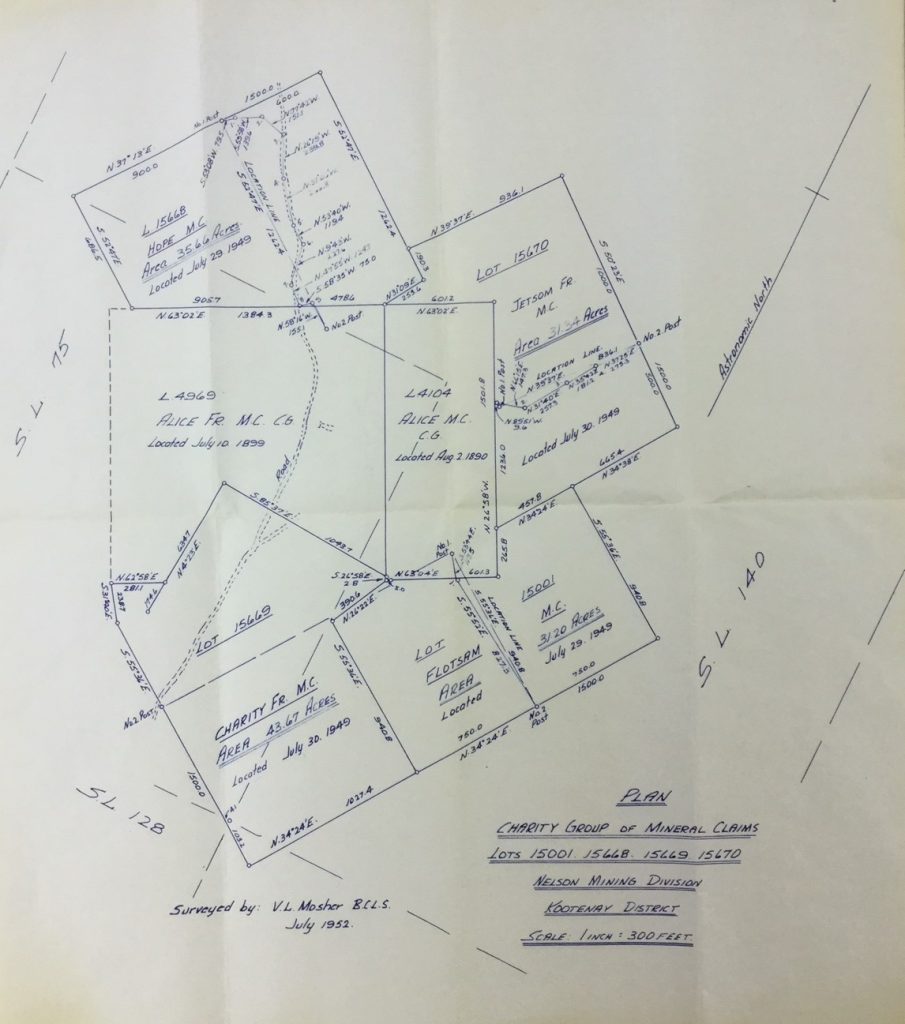

Above is an undated map showing the Alice Mine (the tall narrow rectangle near the centre of the map), the Alice Fraction to the left, and several other early mining claims in the immediate vicinity. It was drawn after 1939 (one of the claims in the upper section is stamped as “cancelled February 1939), but it is definitely earlier than 1949. The map below, prepared in 1952 by local surveyor and engineer Vaughn Mosher, shows both the Alice and the Alice Fraction, but all the surrounding claims have different names from the earlier map and indicates that those claims were located in 1949 – the result, no doubt, of Guy Constable re-acquiring the mine that year and doing some additional investigating in preparation for the work undertaken over the next few years.

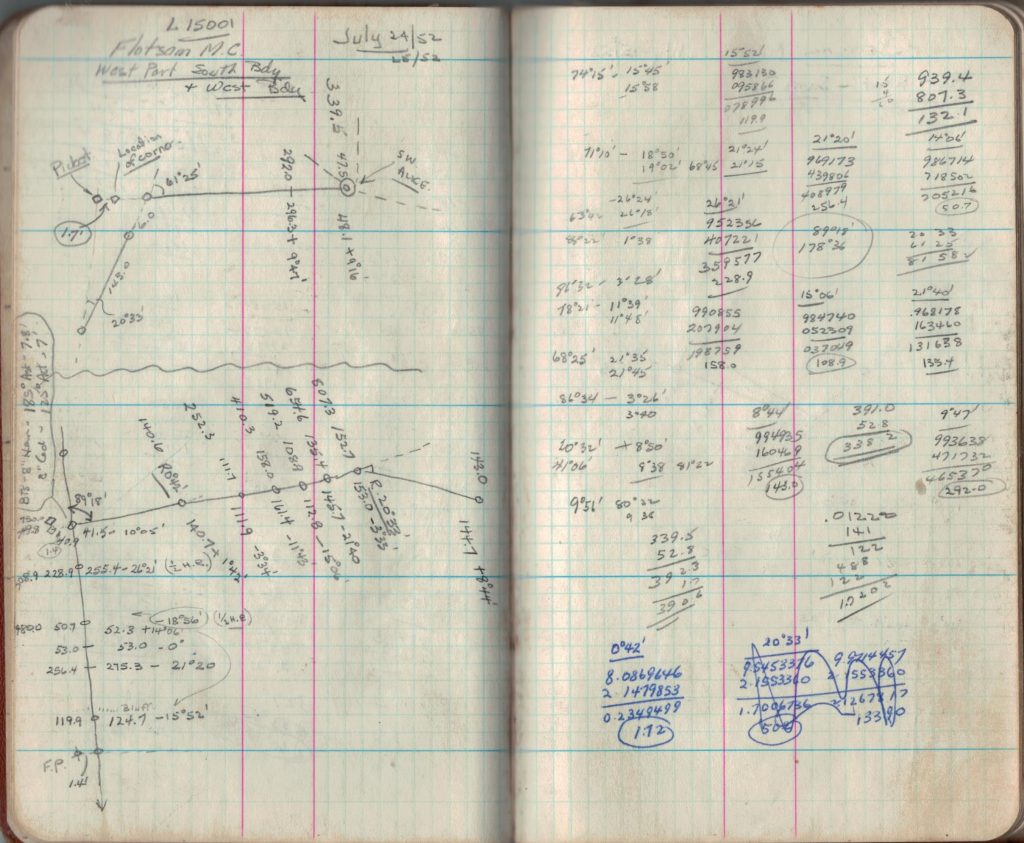

Mosher spent probably considerable time stomping around the claim site – at least, we can assume he did, if the field noteboooks he left are any indication. Several pages in one of them, and scattered pages in others, are filled with sketches and notes regarding the locations and orientations of the various claims in the Alice Group. Here’s a sample of one of those pages:

There were dozens of other mines in the Creston area – seventy-four, according to the 1894 report of the Minister of Mines, and no doubt several others that were located later. Some of the more well known ones include the King, now under Highway 3 through Creston, McPeak and Jennie on Goat Mountain (Jennie, in fact, is shown on the earlier of the two maps above), Elsie Holmes and President at Wynndel, the Spokane mine above Tye, and the Delaware group. In some places, a few tunnels were even dug, but little if anything of value was every taken out.

There was also the Bayonne Mine above Tye on the west side of Kootenay Lake – but that one is worth a whole story all to itself.